I lead the Exoplanets and Planetary Formation Group at NISER Bhubaneswar, where we explore the full lifecycle of planets, from their birth in protoplanetary disks to the emergence of atmospheres and the evolution of their deep interiors. Our research connects exoplanetary atmospheres, astrochemistry, planet formation, and interior physics within a single, integrated framework. By combining state-of-the-art theoretical models, advanced numerical simulations, modern machine-learning tools, and multi-wavelength observations from both ground- and space-based observatories, we seek to uncover how planets form, evolve, diversify, and ultimately become habitable worlds.

Below I highlight recent breakthroughs from my group, spanning exoplanetary atmospheres, astrochemistry, planet-forming disks, and exoplanetary interiors, and illustrating how these interconnected areas together shape our understanding of planetary origins and habitability.

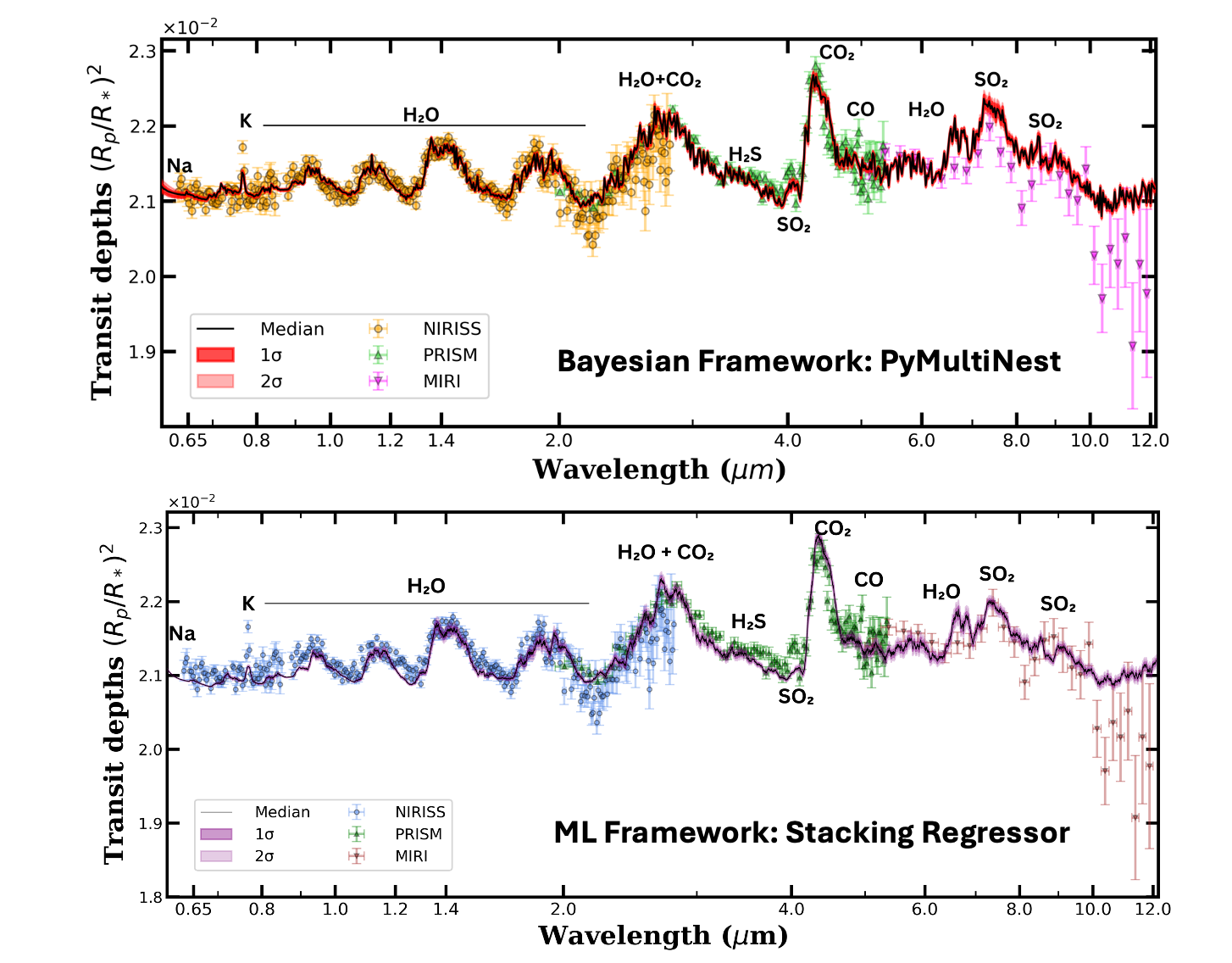

My group has developed NEXOTRANS, a next-generation atmospheric retrieval framework that combines full Bayesian inference with machine learning in a single architecture. NEXOTRANS enables high-precision characterization of exoplanet atmospheres by jointly fitting multi-instrument transmission spectra and retrieving molecular abundances, temperature structures, and cloud properties with high efficiency and accuracy. It is the first comprehensive atmospheric retrieval framework of its kind developed in India.

We have applied NEXOTRANS to the hot Jupiter WASP-39 b using the complete suite of JWST observations from the NIRISS, NIRSpec PRISM, and MIRI instruments. The framework performs a fully consistent fit across all datasets and retrieves molecular abundances, equilibrium-offset chemistry, temperature profiles, and cloud properties with significantly tighter constraints than earlier approaches. A central feature of NEXOTRANS is its dual architecture: the Bayesian engine uses UltraNest and PyMultiNest, while the machine learning engine employs Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, K-Nearest Neighbors, and a Stacking Regressor to accelerate retrievals and cross-validate solutions.

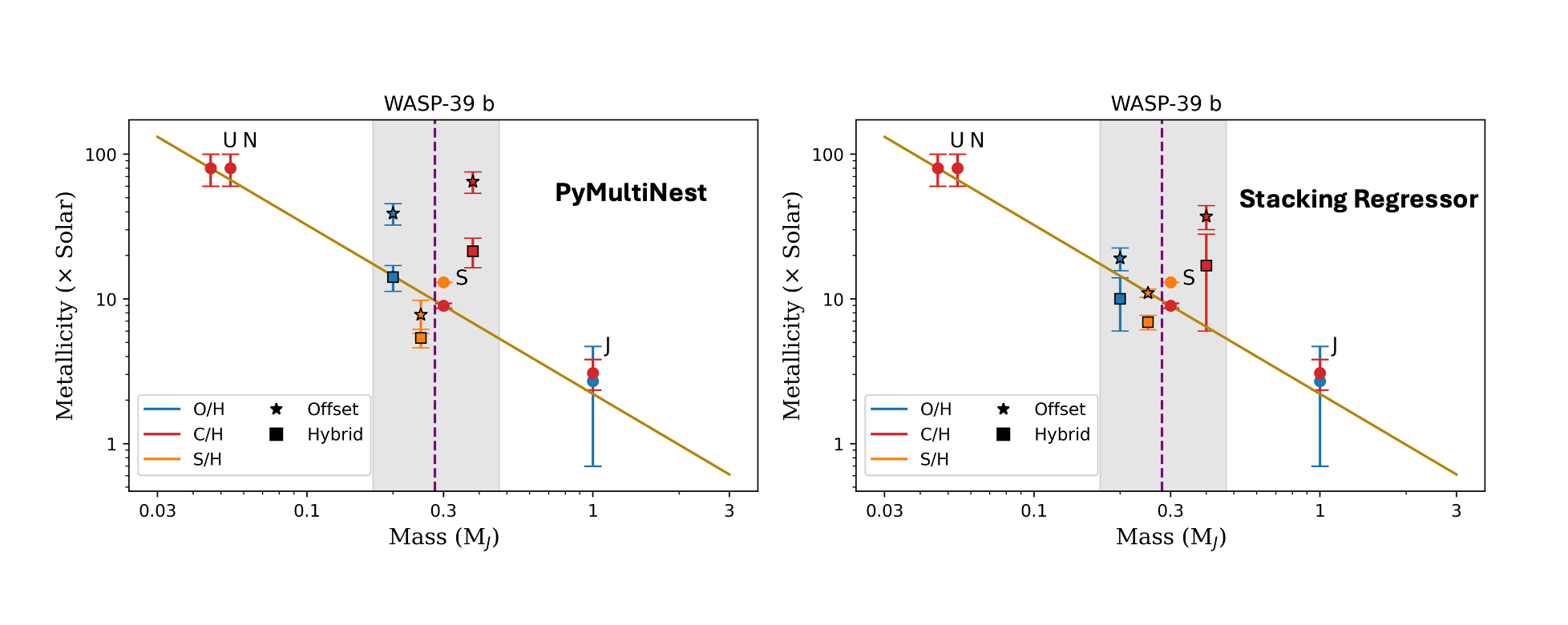

Our analysis also reveals a clear mass–metallicity trend for WASP-39 b, as shown in Figure 2. The retrieved elemental abundances indicate a metallicity enhancement relative to solar values and provide an important benchmark for comparing WASP-39 b to the giant planets in our own solar system and to other JWST targets. Together, these results demonstrate how NEXOTRANS can exploit the full information content of JWST spectra to probe atmospheric diversity and formation pathways.

These atmospheric retrievals pose a fundamental question for exoplanet science: what are the true origins of exoplanetary atmospheres, and how do the diverse elemental compositions we observe in C/H, O/H, and S/H arise? To explore this, we trace the chemical evolution of water and other key volatiles from their formation as ices in the interstellar medium to their transformation within the warm, rocky planet-forming zones around young stars.

To understand the origins of atmospheric compositions in exoplanets, we must follow the trail of molecules back to their earliest environments. This journey begins in the coldest corners of interstellar clouds, where dust grains become coated with ices rich in H2O, CO, CO2, CH3OH, NH3, and a diverse suite of complex organic molecules (COMs). These icy grains are the chemical seeds of new planetary systems. As clouds collapse into protostars and disks, these ices are transported inward, carrying with them the molecular fingerprints that will later shape a planet’s atmospheric C/H, O/H, and S/H ratios.

In my group, we uncover this hidden chemical evolution using a combination of advanced modeling and cutting-edge observations from JWST. We track how simple ices transform into complex organics and how these molecules assemble the chemical foundations of habitable worlds.

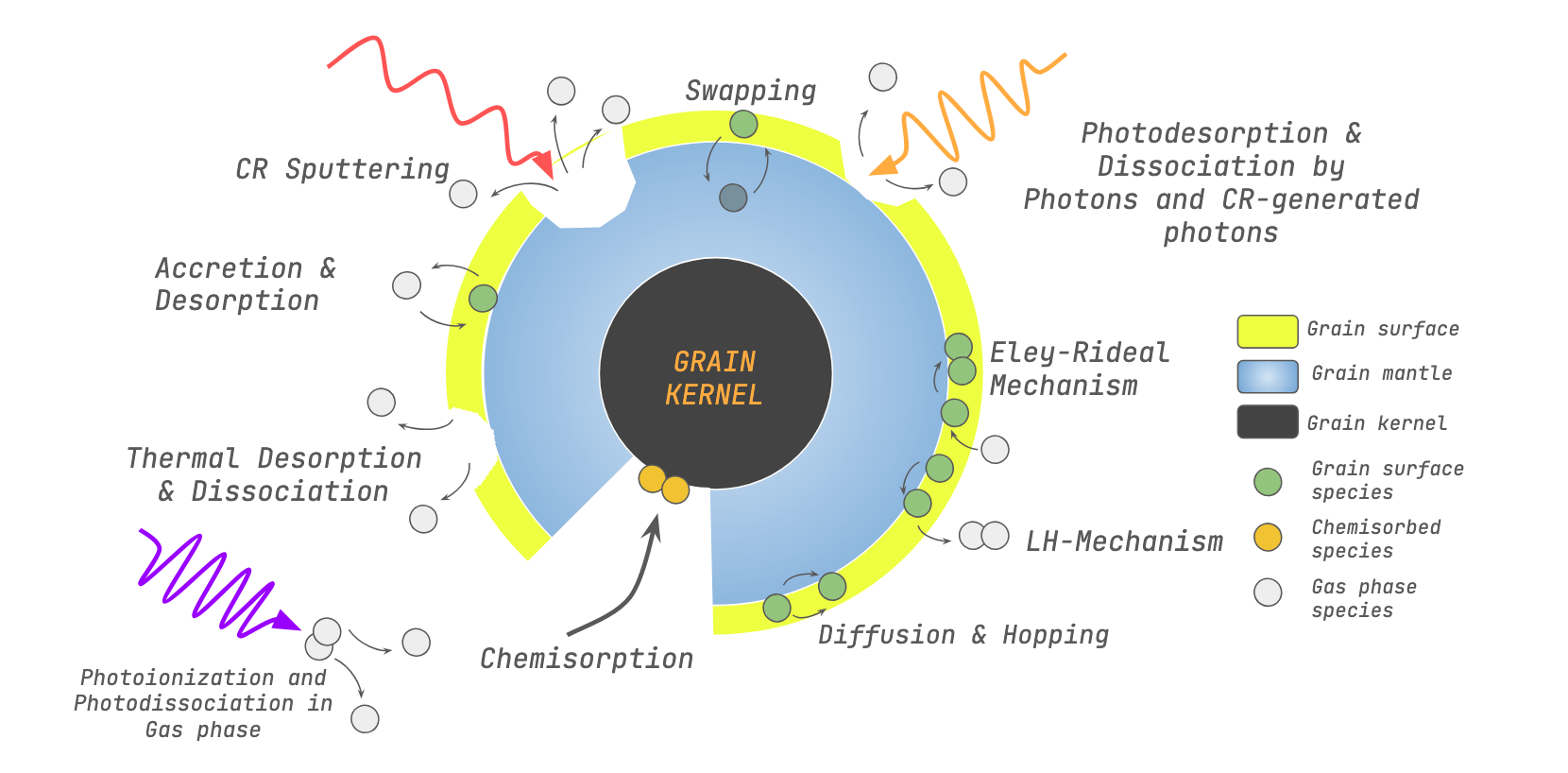

On the modeling side, we have developed PEGASIS, a fast, flexible three-phase astrochemical code that follows chemistry from pre-stellar cores to planet-forming disks. PEGASIS captures both diffusive and nondiffusive chemistry and allows the ice mantle to be either inert or chemically active, enabling us to simulate a broad range of physical environments. Figure 3 shows a schematic of the rich network of ice processes that PEGASIS tracks — accretion, diffusion, photodissociation, surface reactions, mantle chemistry, and desorption.

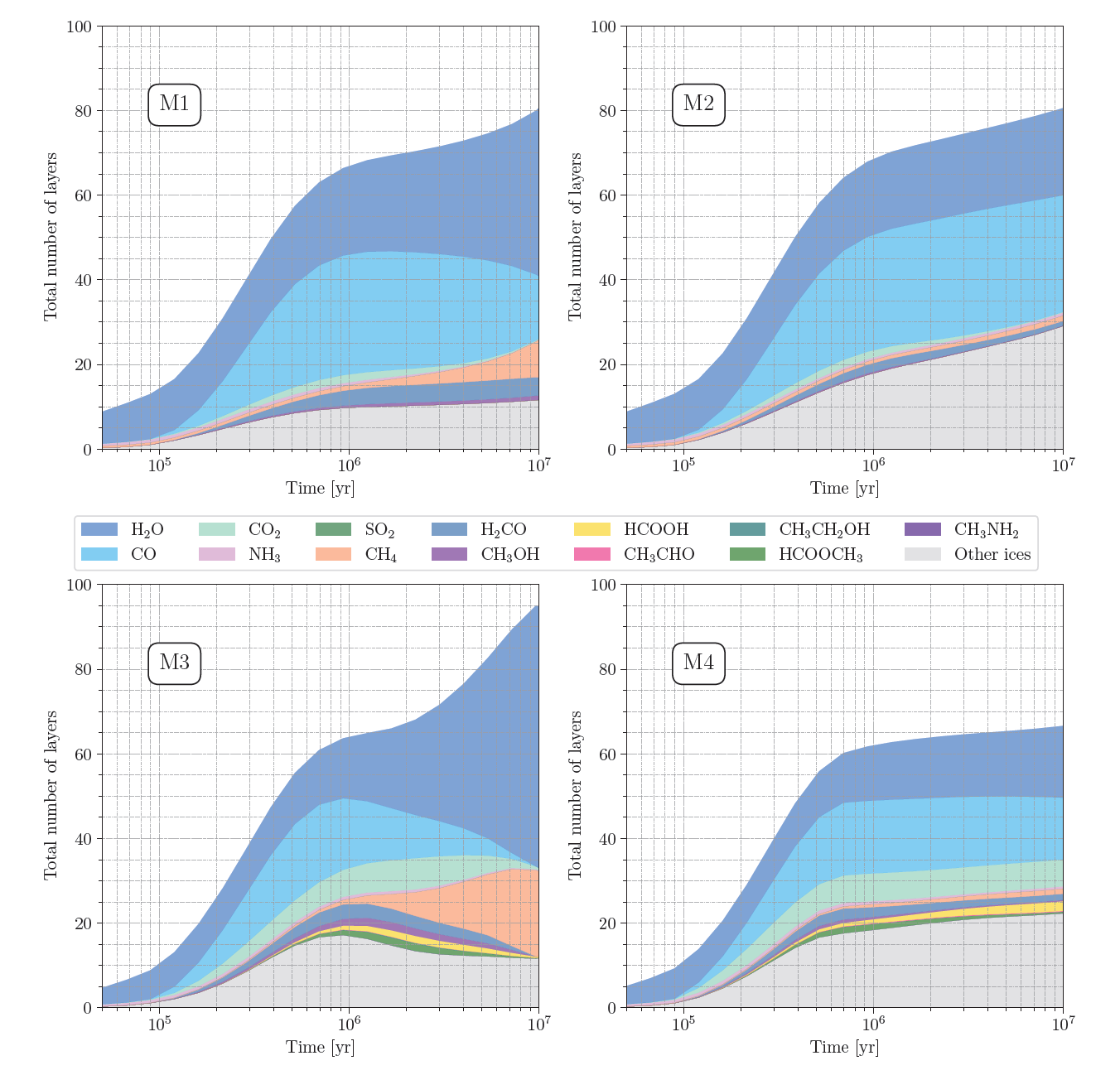

When nondiffusive processes are included, PEGASIS predicts a dramatic boost in the formation of COMs on both grain surfaces and within the ice mantle. This effect is shown in Figure 4, which highlights how total ice thickness evolves across several chemical models. These results demonstrate that the microphysics of ice chemistry leaves macroscopic signatures that are now directly detectable with JWST, revealing how the earliest organic reservoirs form.

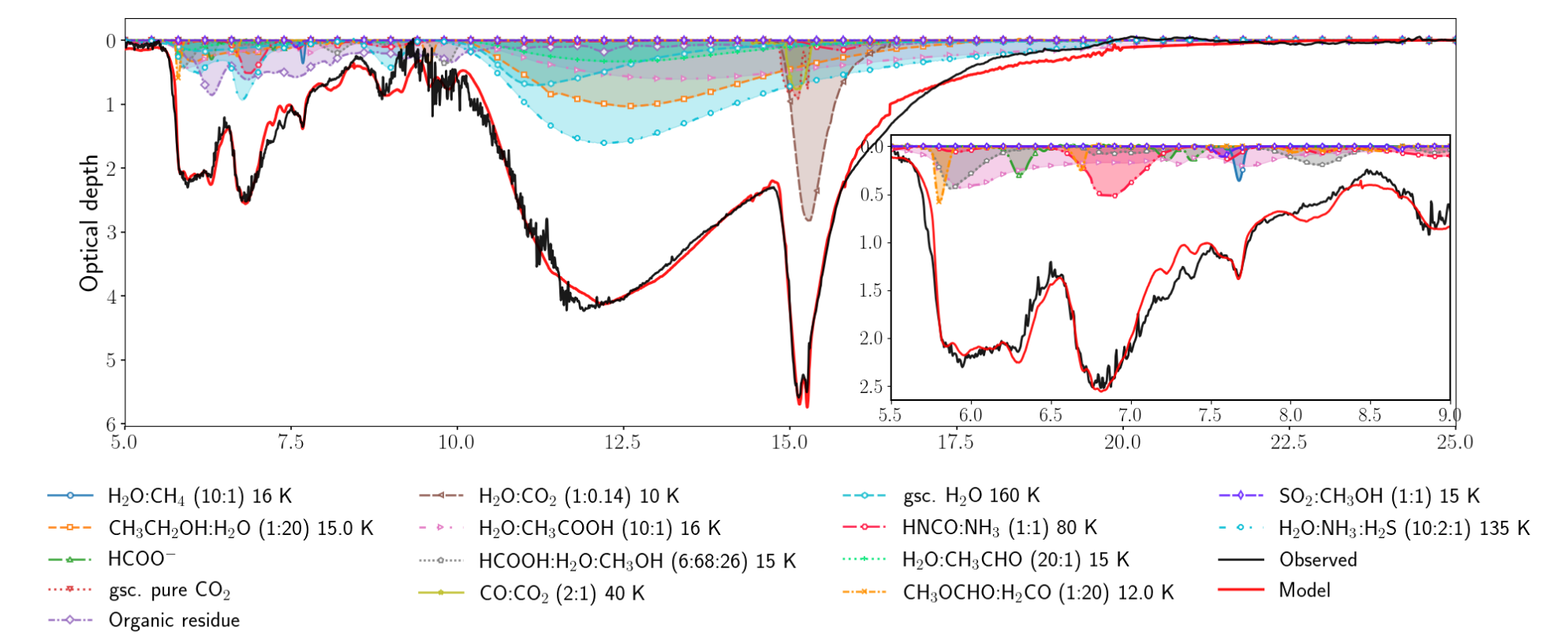

On the observational side, we developed INDRA (Ice-fitting with NNLS-based Decomposition and Retrieval Algorithm), a fully Python-based global ice-analysis framework optimized for JWST. INDRA removes the continuum and silicate features and uses weighted Non-Negative Least Squares to decompose JWST/MIRI spectra from 5 to 25 µm into contributions from multiple ice species.

Applied to the protostar NGC 1333 IRAS 2A, INDRA recovers expected simple ices and COMs, and also reveals new contributions from CO2, NH4+, and up to about 9.6 percent organic refractory material. These broad features between 5.5 and 11 µm point to large, complex molecules containing C=O, O–H, N–H, and C–H groups, giving us new insight into how chemical complexity emerges in star-forming regions.

Together, PEGASIS and INDRA provide a unified framework connecting the microphysics of grain-surface chemistry to the infrared ice signatures unveiled by JWST. By integrating theory and observations, our work traces how complex organics arise in the earliest stages of star and planet formation and how these molecular building blocks of life are delivered to planet-forming disks.

The next step is to follow these chemically enriched ices and gases into the birthplaces of planets and examine how they shape the compositions of emerging worlds.

The chemically enriched ices and gases traced in interstellar clouds and protostars do not remain static. As material flows inward, these molecules are delivered into protoplanetary disks, where dust, ice, and gas interact to build the foundations of new planetary systems. The chemistry within these disks determines the volatile reservoirs that young planets inherit and ultimately shapes the elemental ratios we observe in their atmospheres. To understand this inheritance, my group combines high-resolution ALMA observations with detailed chemical modeling to map the physical and chemical architecture of planet-forming regions.

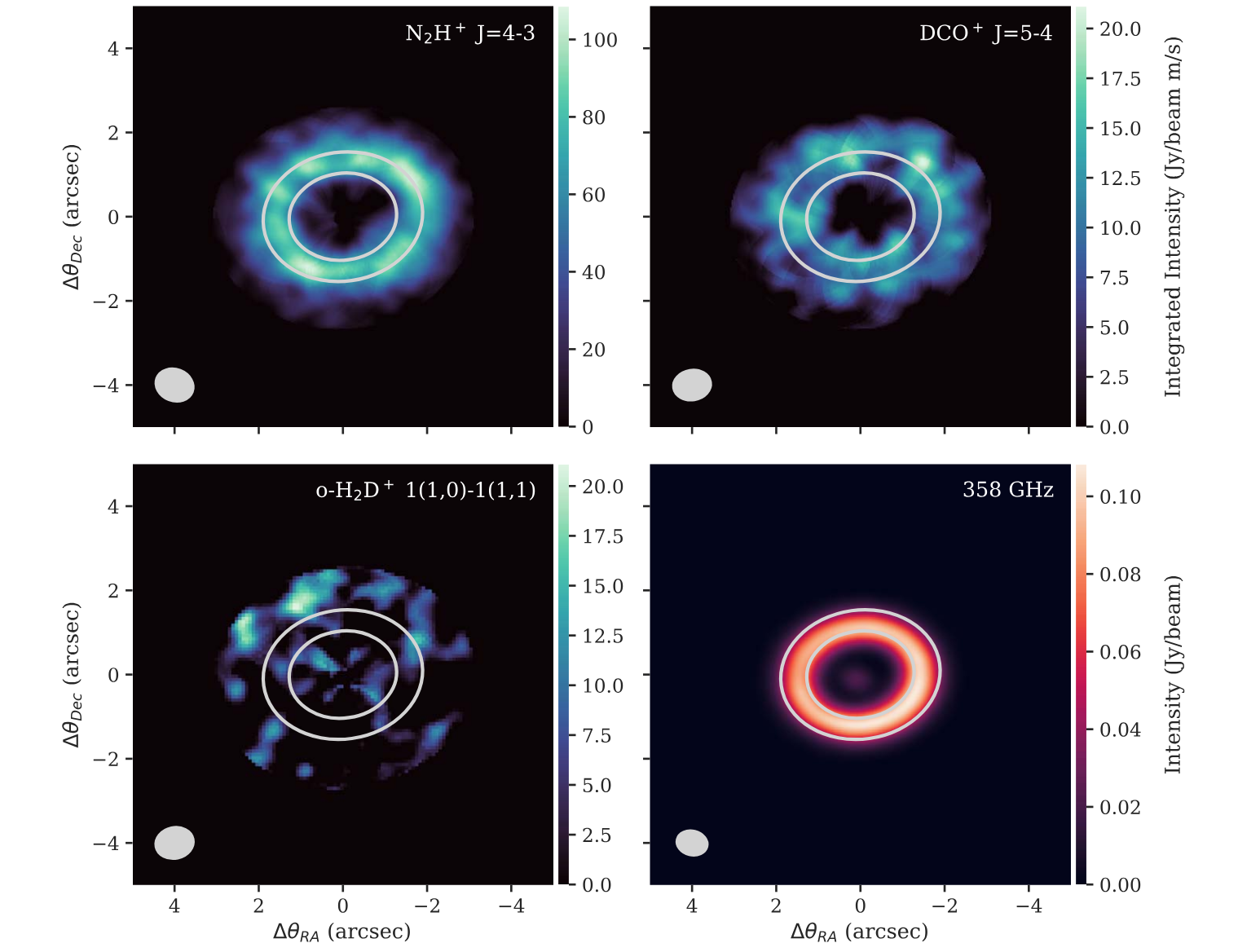

One of the most striking examples is the triple T Tauri system GG Tau A, which hosts a massive circumbinary ring and an extended outer disk. This system offers a rare opportunity to study the coldest, most chemically pristine regions where planetesimals begin to form. Using ALMA Band 7, we mapped emission from N2H+ and DCO+, along with upper limits for H2D+, 13CS, and SO2. As shown in Figure 6, N2H+ and DCO+ extend well beyond the dust ring, revealing the presence of CO-depleted, cold gas, while H2D+ remains undetected. These tracers isolate the icy midplane layers where grains grow, accumulate volatiles, and eventually form the building blocks of planets.

By combining these maps with additional transitions and PEGASIS astrochemical modeling, we explored how the abundances of N2H+, DCO+, and H2D+ depend on cosmic-ray ionization, stellar UV radiation, and the underlying C/O ratio. We find that these ions are most sensitive to cosmic-ray ionization, with a preferred rate of about 10−18 s−1. The resulting temperatures, 12 to 16 K, lie below the CO freeze-out threshold, confirming that GG Tau A hosts one of the coldest and chemically richest rings known.

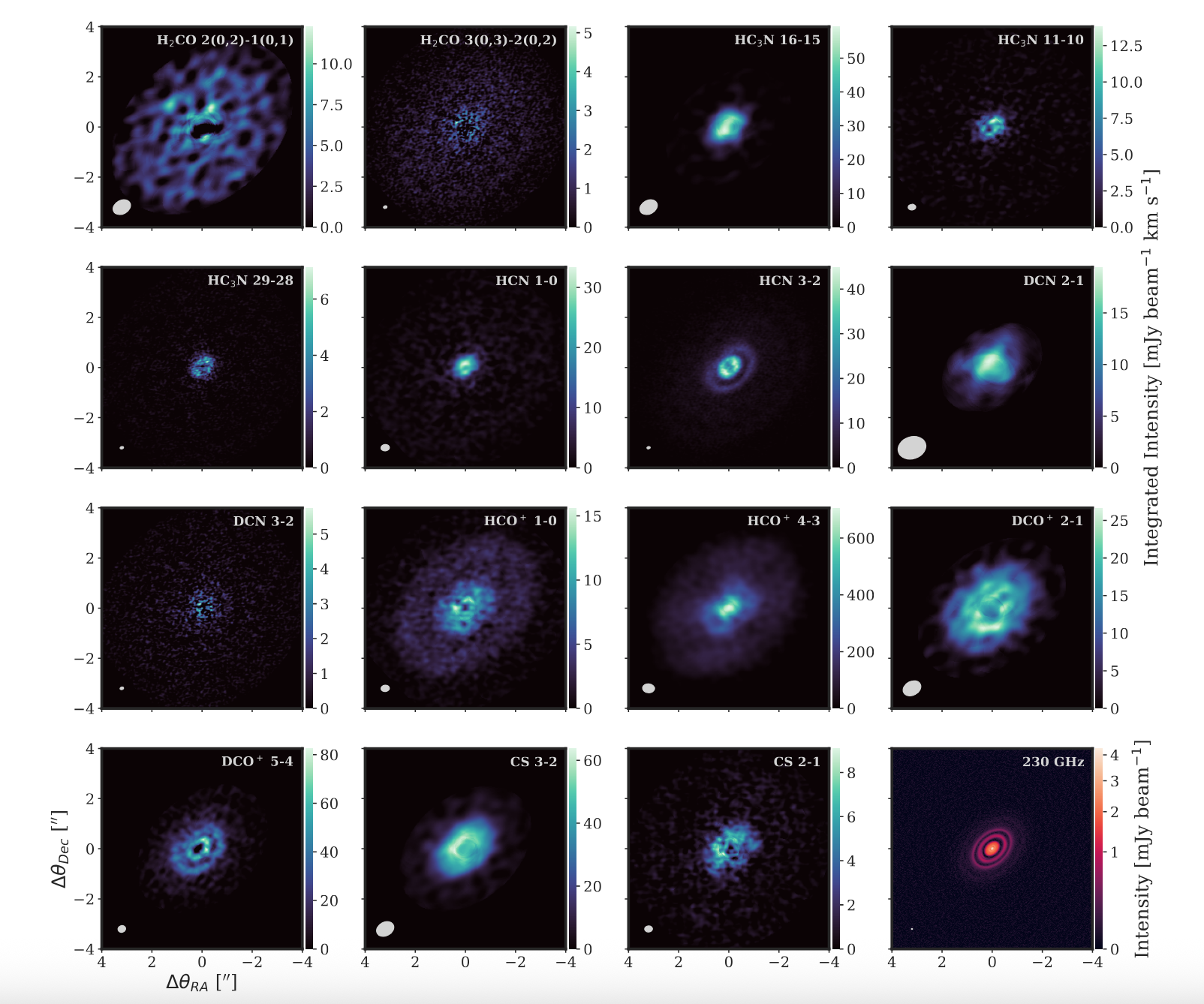

We also extend our analysis to the nearby Herbig Ae disk HD 163296, a benchmark system for planet formation. By combining ALMA observations across Bands 3, 4, 6, and 7 with our retrieval tool DRIVE, we derived radial distributions of column density and excitation temperature for numerous species, including HCO+, DCO+, HCN, DCN, CS, HC3N, H2CO, CH3OH, HNCO, and NH2CHO. We then used PEGASIS with varying C/O ratios to interpret these molecular rings in terms of elemental budgets and volatile transport.

Our models favor a disk-averaged C/O ratio of about 1.1, consistent with earlier predictions. We obtain the highest-resolution DCO+ map of this disk to date, revealing a striking triple-ring structure that mirrors the dust rings. We also place strong upper limits on NH2CHO and HNCO, indicating that these complex organics likely form on grain surfaces with only limited desorption into the gas. These molecular rings and gaps encode the movement of volatiles, the build-up of organics, and the chemical environments that future planets will inherit.

Together, our studies of GG Tau A and HD 163296 show how high-resolution ALMA observations, interpreted with PEGASIS and DRIVE, reveal the physical and chemical landscape of planet-forming disks. Combined with our work on interstellar ices and exoplanetary atmospheres, these results complete the link from star-forming clouds to fully formed planets and the atmospheric compositions we observe today.

To complete this story, we now turn inward, into the deep interiors of planets, where the earliest chemical signatures are reprocessed and transformed.

Once planets assemble from chemically enriched disks, their evolution does not stop at the surface. Deep beneath their atmospheres, the interior structure, cooling history, and volatile release all shape the atmospheres that telescopes like JWST are now beginning to probe. Super-Earths, which span the size range between Earth and Neptune, are the most common planets in the Galaxy. Their atmospheres are becoming accessible, but their interiors remain hidden. To connect disk chemistry to atmospheric composition and habitability, it is essential to understand what happens inside these worlds as they cool, differentiate, and exchange volatiles with their surfaces and atmospheres.

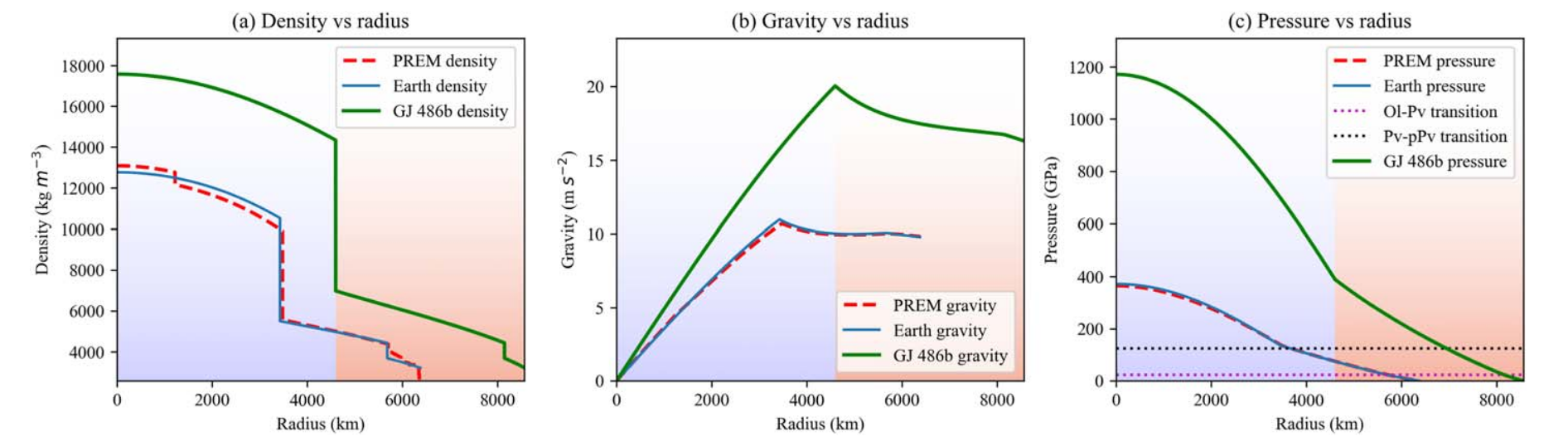

As a first step toward this interior–atmosphere connection, we investigated the super-Earth GJ 486b using SERPINT, a one-dimensional, self-consistent model of planetary interior structure and thermal evolution. Assuming an Earth-like bulk composition, we derived the planet’s internal density, gravity, and pressure profiles and compared them with Earth and the PREM reference model. Our results show that GJ 486b hosts a core roughly 1.34 times larger than Earth’s and reaching pressures of about 1171 GPa, indicating a compact and iron-rich interior.

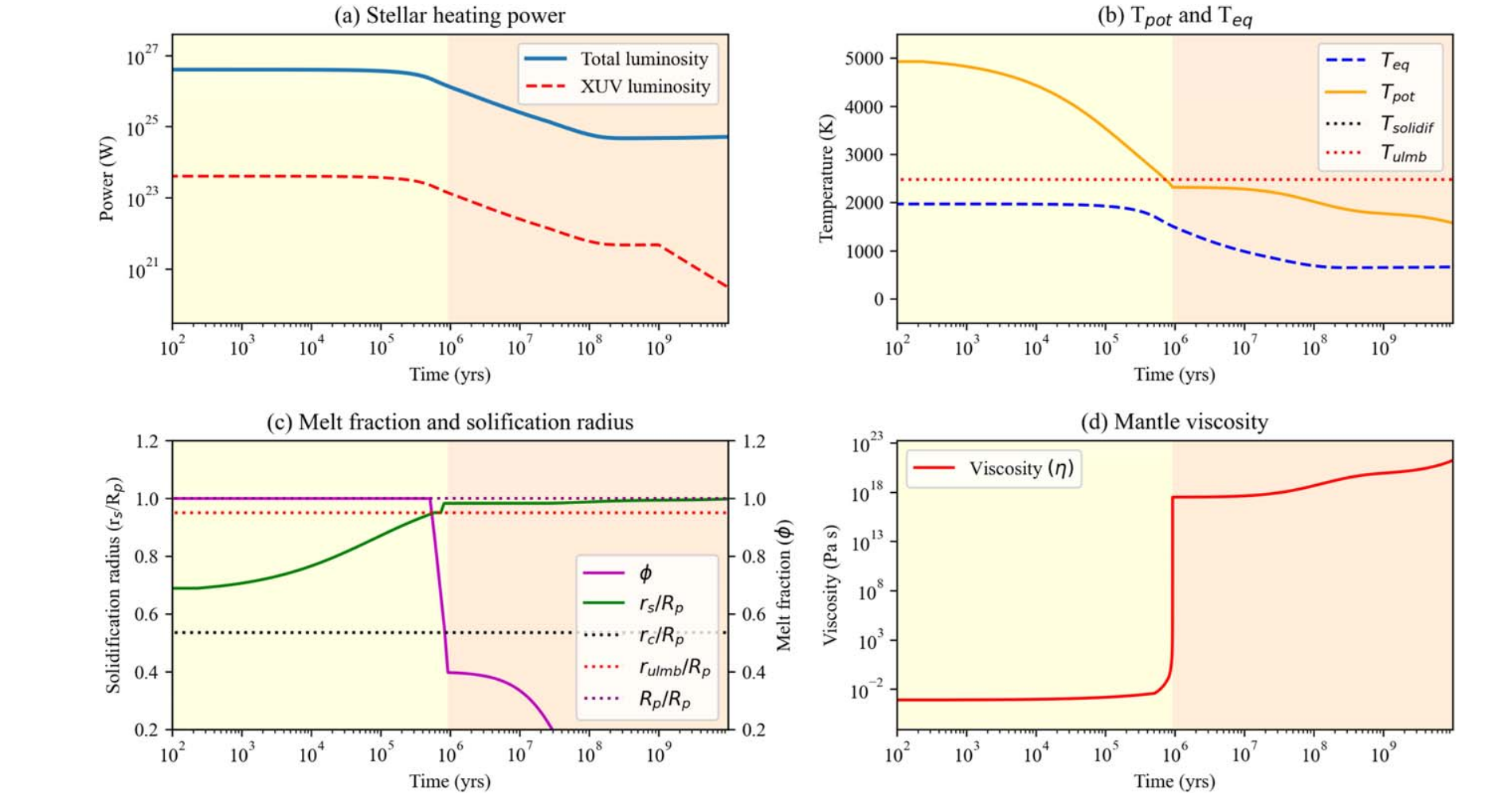

We then modeled the planet’s thermal evolution to follow how it cools from an early magma-ocean phase to a fully solidified interior. The SERPINT calculations predict that the mantle cools and solidifies within about 0.93 Myr. During this period, the evolving stellar luminosity, particularly in the high-energy XUV range, plays a major role in shaping the planet’s surface and atmosphere.

As the magma ocean cools, water trapped in the molten interior is gradually released to form a transient, steam-rich atmosphere. Photolysis of this water vapor, followed by the escape of hydrogen, results in the buildup of oxygen and the creation of a secondary atmosphere that is enriched in both water and oxygen. These processes are illustrated in Figure 9, which shows the evolution of stellar luminosity, mantle temperature, melt fraction, viscosity, and radius structure across the planet’s early history.

This work on GJ 486b demonstrates that interior structure, thermal evolution, volatile outgassing, and atmospheric escape are deeply interconnected for rocky and super-Earth-type planets. When combined with the high-quality spectra now being delivered by JWST, interior models such as SERPINT provide a powerful way to link interior processes to atmospheric composition, closing the loop between disk chemistry, planetary formation, interior dynamics, and the atmospheres we can observe today.

Across these projects, my group unifies exoplanetary atmospheres, astrochemistry, planet formation, and planetary interiors into a single narrative of planet formation and evolution. By combining NEXOTRANS retrievals of JWST spectra, PEGASIS and INDRA astrochemistry, DRIVE-enabled ALMA disk studies, and SERPINT interior modeling, we trace the journey of volatiles and organics from interstellar ices to planet-forming disks, through planetary interiors, and back into observable atmospheres. This integrated, end-to-end approach is central to answering one of the most compelling questions in astrophysics and planetary science: how planets form, evolve, and become habitable.